A moment can mean many things to many people. It could refer to a certain perceived set of extant subject matter, living or inanimate, interacting in real time and possibly worthy of the well-timed snap of a camera shutter.

It could also refer to a larger cultural moment, articulated by the cumulative sum of countless smaller moments, rendered as images, articles, films, speeches, poems, fashion pieces, paintings, dance, music; all the tools that provide the stitches and threads; the fabric of what we call culture.

But what of African-American culture—or how this concept alone places these powerful tools and the artists who use them into a paradigm, one that remains marginalized from the dominant culture and the supremacy of its reigning body politic? Could there be a moment that catalyzes Black culture through a high-art lens? There is, more recently, a series of observations regarding what some are calling a Black Renaissance, a humble annihilation of the barriers—both physical and metaphysical—that continue to segregate and compartmentalize human achievement.

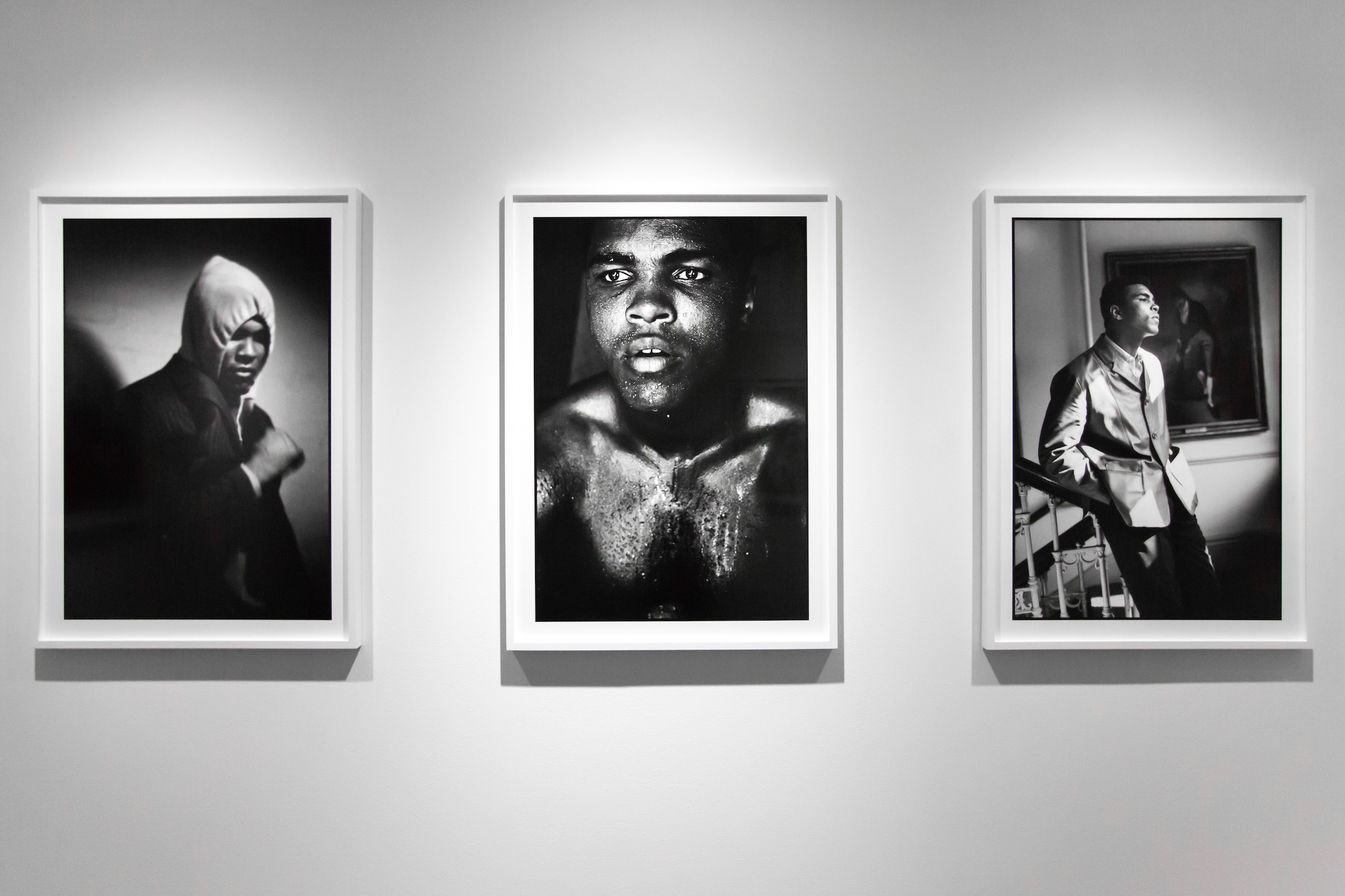

Gordon Parks: Selections from the Dean Collection, a career-spanning exhibition comprised of iconic and intimate works by the eponymous and incomparable 20th century photographer, writer and film director, opened on Thursday, April 25 at the Ethelbert Cooper Gallery of African and African American Art at the Hutchins Center, located in the heart of Harvard Square in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

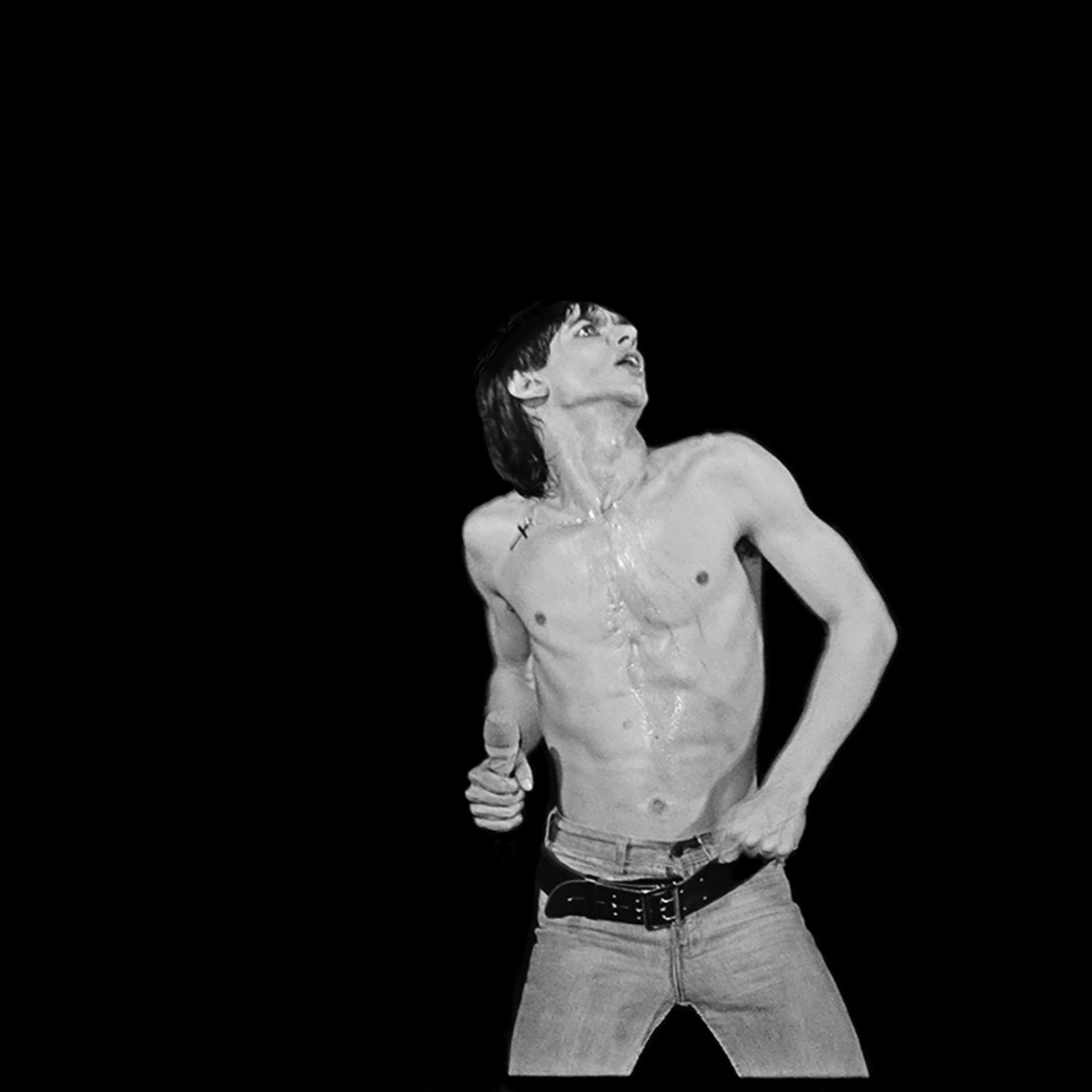

The better part of four decades is represented in the show, ranging from Parks’s early government work in the 1940s through his fashion work in the '70s. Throughout his career, Parks fixed his lens on the men and women of Black America, often deemed invisible by the media (the forgotten Norman Rockwell subjects), and, later, major artists and public figures: Malcolm X, Alberto Giacometti, Muhammad Ali (extensively), Martin Luther King Jr., and Eldridge Cleaver and his wife, Kathleen, who Parks photographed while the pair—both Black Panthers—was exiled in Algeria in 1970.

Decades later, another power couple stepped into their shoes, afros and berets to recreate this image with the assistance of celebrated photographer Jamel Shabazz for Cultured's June 2018 cover story.

“I was moved by Gordon Parks as a renaissance man, which is how I’ve always seen Swizz,” says the singer-songwriter (and so much more) Alicia Keys of her husband. Roughly seven years ago, Keys purchased two of Parks’s works, one of Mohammed Ali and the other of a 17-year-old gang leader in Harlem. “When I thought of a gift for Father's Day, I thought of those two spirits: a fighter—one deeply rooted in culturally shifting and molding and speaking the truth—and the gangster who is absolutely taking no shit. And all that together is part of the man I know.”

Keys, the effusively radiant music legend, host, actor and philanthropist, and the producer, art collector and recent Harvard Business School graduate, Kasseem Dean—a.k.a. Swizz Beatz—together and in conjunction with the Gordon Parks Foundation, amassed what is now the largest privately owned collection of Parks’s images. This effectively anoints the comprehensive premiere show at Cooper Gallery the first major exhibition by an African American photographer, showing in a gallery dedicated to African American artists and featuring a wide range of important works owned exclusively by African American collectors.

“A lot of people talk about the culture, but don’t own anything from the culture,” Swizz offered. “We should be the leaders of our culture.”

If this weren’t enough to push Gordon Parks: Selections from the Dean Collection into the realm of the historic, the opening of the exhibition was preceded by day one of “Vision & Justice: A Convening,” a two-day, don’t call it a conference, conceived and curated by Sarah Lewis, Assistant Professor of History of Art and Architecture and African and African American Studies at Harvard. The convening was hosted by the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study with support from the Ford Foundation, the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research, the Harvard Art Museums and the American Repertory Theater.

Executive Director of The Gordon Parks Foundation, Peter W. Kunhardt, Jr., introduced Swizz early in the proceedings, and shared a quote from Parks, pulled from his 1968 LIFE Magazine article. The piece was commissioned by Kunhardt’s grandfather, then the managing editor at LIFE, who also started the GPF and remained good friends with Parks until they died just weeks apart in 2006. The quote was pulled from Parks’s legendary photo essay, The Negro and the Cities: The Cry That Will be Heard, which chronicled the trials and tribulations of Harlem’s Fontenelle family:

“What I want, what I am, what you force me to be is what you are, or I am you, staring back from a mirror of poverty and despair, of revolt and freedom. Look at me and know that to destroy me is to destroy yourself. You are weary of the long hot summers. I am tired of the long hungered winters. We are not as far apart as we may seem. There is something about us that goes deeper than blood or black and white, in our common search for a better life and a better world.”These words showcase Parks’s literary sensibilities as well, and served as an ongoing reference point for the Gordon Parks Essay Prize, which was awarded to three worthy recipients. The Dean Collection promised to match the $5,000 grants awarded to the winners, an announcement which elicited a rousing ovation from the overflowing Radcliffe audience.

Lewis, who also wears many hats (curator, author, journalist), brought together an impressive role call of prolific and essential black artists working in the world right now. Participants included David Adjaye, the British architect who designed Harvard’s Cooper Gallery, the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, and the upcoming Studio Museum in Harlem. Adjaye was joined on stage by Lewis and the artist Carrie Mae Weems, perhaps best known for her striking, award-winning self-portraits—gothic depictions of her elegant and formidable body juxtaposed defiantly against landmark American buildings, stately patriarchal expressions that throughout history have represented, consciously or not and to varying degrees, exclusion and intimidation to black bodies and souls. Adjaye’s Egyptian-influenced NMAAHC on the National Mall and its close proximity to the Washington Monument (more phallic and white than ever, it seems), is an architectural expression of this same creative confrontation.

Weems ended day one with a devastating performance of Grace Notes: Reflections for Now, initially created and performed as a healing memorial for the Emanuel 9, who were senselessly massacred by a white supremacist in Charleston, SC in 2015. Weems also recited the hallowed names of victims of police shootings over live cello and piano performances and videos of Charlottesville’s tiki-torch terrorists. Much of the performance revolved around Sophocles’s tragic play Antigone, which is being leaned on in various creative circles (Antigone in Ferguson) to interrogate who decides whose bodies have value and why.

The 2018 Infinity Award winner Alexandra Bell, soon to be featured in the upcoming Whitney Biennial, impressed earlier that same day with a video and remarks concerning her celebrated Counternarratives series, in which the multidisciplinary artist sliced up, marked, remixed and redacted seemingly benign New York Times articles, highlighting their implicit and explicit biases and reimagining them with new, biting, satirical headlines. “I’m not interested in diversity,” Bell said at one point. “I’m more like, 'Burn it down.'”

Over the course of Thursday and Friday, the Radcliffe Institute would host celebrated voices such as Ava DuVernay, Hank Willis Thomas, Theaster Gates, LaToya Ruby Frazier, and writer, curator and activist Kimberly Drew. The backdrop for “Vision & Justice: A Convening,” was the summer 2016 Vision & Justice issue (223) of Aperture Magazine, which was guest-edited by Sarah Lewis; the issue would go on to inspire a core curriculum class at Harvard, taught by Lewis, and a free reprint titled Vision & Justice: A Civic Curriculum.

The dream is that such a curriculum should extend beyond the walls of an art gallery or the classroom of an Ivy-league institution, and become required reading for all Americans. It’s figures like Swizz and Keys who could be this catalytic bridge. Like Frederick Douglass, the most photographed man of the 19th century—he graces the front of the Vision & Justice reprint—the pair understands the power of photography to dramatically shift narratives, to capture a moment, whether big or small, tragic or transcendent.

“I think this moment is so important, as you see us hand in flesh; we have to participate in it, because it’s not just another thing—it’s the thing,” offered Swizz, during the after-exhibition dinner. Looking around the pillared, canary yellow room, at the various tables Thursday evening, one would see a picture of Black Excellence and feel the future possibility that such a thing might one day be deemed excellence. Period.

“One thing Swizz taught me is how to be present,” Keys added, right as Shabazz captured a spontaneous group photo of Vision & Justice’s many participants. “It’s important to be thinking about the future and planning for it, but it’s just as important to be in the moment. We don’t know what’s promised to us or guaranteed, so take it in. Just this moment, Swizz leaned over to me and said, ‘I feel like I’m in a dream.’ We are in a dream—guess what, we are the dream. We’re all the dream.”