A Zeus, a Jesus, a jester… or is it an evil clown? Actually, it’s President Barack Obama (yes, we can still call him that for a few more precious days)—seen through the lens (literally) of artist Carrie Mae Weems. “The Obama Project” (2016, video installation), on view at The Ethelbert Cooper Gallery of African & African American Art at Harvard University is part of Weems’ ambitious and electrifying exhibition “Carrie Mae Weems: I once knew a girl…” (through Jan. 7) and couldn’t be more timely as we contemplate the current political climate. Weems, through 52 works of photography and video installation, critiques and lays bare (again, sometimes literally) societal constructs around race, gender, power, and the institutions that capture and select history.

Weems, an internationally acclaimed artist, employs narrative through both static and moving pictures, often employing herself as the silent observer or casual participant. The exhibition is laid out in three sections—Beauty, Legacies, and Landscapes—from Weems contemplating herself through the eyes of historically canonized white male painters in photographs that line the front ramped corridor to the equally suggestive images and video installations reacting to art historical and cultural norms displayed along further hallways and smaller screening rooms. The shadowy, almost darkened spaces give one the feeling of a voyeur, and at the same time foster a sense of intimacy between artist and viewer.

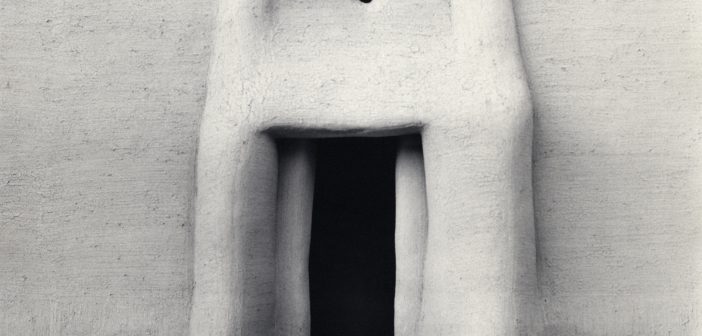

“The Considered, See Bergman” (2012) Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

In the section “Beauty,” gallery director Vera Ingrid Grant, who curated the show in collaboration with Weems, describes via wall text how “Weems visually narrates the human consequences of our socially constructed enclosure within dominant Western art culture.” Progressive MFA programs place this notion front and center—my own program was no exception. Ever since, I have been on the alert for what could be called “status quo” art—beautiful, even intellectually compelling and culturally relevant, but within the confines of the expected and the accepted.

Weems reminds viewers that nothing should be taken for granted. In appropriating constructs and reacting to them, Weems shows us how to deconstruct these notions. Through this process, we have the opportunity to revise beloved beliefs and prejudices—some unconscious—delivering us to a new way of seeing, or at the very least, of questioning.

“Not Manet’s Type” (1997) Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery New York.

In “Splattered 1” (2016, acrylic paint and ink on canvas), a Pollock-like frenzy of paint in primary colors constellates what on closer inspection appear to be carefully placed threads of paint, and if one attaches symbolic meaning to color, then red, white, and blue (America’s colors) are in chaos, with yellow symbolizing fear, and black and white potentially representing race. Weems takes this notion further with “Splattered 2” (2016, silkscreen and acrylic paint on paper)—a photographic image of what one assumes are slaves working the land; the image overlaid by Pollock-like splatters of black paint, sparsely strewn across the surface.

The aforementioned installation “The Obama Project” includes three looped videos reflecting upon the Obama presidency—with images of Obama altered to reflect the many racially charged projections he has endured, along with images of police brutality against African Americans, including the resulting psychological damage to children. The wall text names it as “contemporary state violence relentlessly perpetrated on our public streets.” This is contrasted with the joyful expressions of children’s coloring on larger-than-life pages from Obama-themed coloring books. Hope and oppression are wary bedfellows indeed.

Finally, in the section “Landscapes, “Weems takes us to architectural monuments, placing herself in front of buildings such as the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Galleria Nazionale D’Arte Modern (Rome), The Louvre (Paris), and the British Museum (London)—she is a sole figure in black, somber against the stark, imposing structures. This, in contrast to images of the Jewish Ghetto and a haunting image of the balcony where Mussolini stood in Rome—a chilling image to contemplate in a dramatically shifting American political landscape. The video installations are equally haunting and evocative, and draw upon the same themes.

“Carrie Mae Weems: I once knew a girl…” is a rare opportunity to see the thoroughly engaging and thought-provoking work of one of today's most relevant artists, with some works on view for the first time. See it before it closes Jan. 7 at the Ethelbert Cooper Gallery of African & African American Art at the Hutchins Center, Harvard University. For more information, visit www.coopergalleryhc.org or call 617-496-5777.

- ͞Not Manet’s Type͟ (1997) Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery New York.

- “The Considered, See Bergman” (2012) Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

- “The Edge of Time – Ancient Rome” (2006) Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

- “Philadelphia Museum of Art – Philadelphia” (2006) Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

- “Slow Fade to Black II (Josephine Baker)” (2009-2011) Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery New York.

- “Not Manet’s Type” (1997) Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery New York.

- “The Shape of Things” from the Africa series (1993) Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.